In this article we’re going to discuss two integral facets of sound performance and how these two impact on, and for many athletes are mistaken for, each other.

We are talking about intensity and economy. Both of which can either make or break your race. One is developed in training and one is enhanced by discipline and fitness however is influenced by knowledge and effects race strategy.

When we discuss the term ‘running economy’ we are referring to a mix of physiological and biomechanical factors that can positively or negatively influence energy utilisation when we run at a set speed or intensity.

We are talking about intensity and economy. Both of which can either make or break your race. One is developed in training and one is enhanced by discipline and fitness however is influenced by knowledge and effects race strategy.

When we discuss the term ‘running economy’ we are referring to a mix of physiological and biomechanical factors that can positively or negatively influence energy utilisation when we run at a set speed or intensity.

The less oxygen you consume at a set speed, the more economical you are said to be, and the longer you will be able to stay at that speed. Added to that, the more economical you are at a given speed, the faster you will be able to go, albeit that this will be limited by VO2 Max, which is the maximum volume of oxygen measured in millilitres per kilogram of body weight per minute.

If we take two runners of equal capacity, and equal body mass, running at the same speed, the runner with the greater running economy will use less oxygen and therefore less energy. Unsurprisingly, there is a strong link between running economy and distance running performance.

There are a number of factors that affect running economy including, but not limited to metabolic adaptations within the muscle, the ability of the muscles to store and release elastic energy, strength training, altitude training, gear choice and more efficient running mechanics.

In order to achieve good running economy we need to be practiced and physiologically able to sustain it, which is where consistent application of training comes in.

Intensity is one of the most fundamental and important variables in the training of distance runners. In lay terms, intensity is simply how hard you’re running relative to how hard you’re capable of running.

There are several different ways in which we can monitor and and moderate our intensity, including, but not limited to pace, heart rate, relative perceived exertion, experience, and breathing. And here is where running economy and intensity overlap.

If we take two runners of equal capacity, and equal body mass, running at the same speed, the runner with the greater running economy will use less oxygen and therefore less energy. Unsurprisingly, there is a strong link between running economy and distance running performance.

There are a number of factors that affect running economy including, but not limited to metabolic adaptations within the muscle, the ability of the muscles to store and release elastic energy, strength training, altitude training, gear choice and more efficient running mechanics.

In order to achieve good running economy we need to be practiced and physiologically able to sustain it, which is where consistent application of training comes in.

Intensity is one of the most fundamental and important variables in the training of distance runners. In lay terms, intensity is simply how hard you’re running relative to how hard you’re capable of running.

There are several different ways in which we can monitor and and moderate our intensity, including, but not limited to pace, heart rate, relative perceived exertion, experience, and breathing. And here is where running economy and intensity overlap.

If we consider the relative intensities for racing, we first need to understand the concept of threshold.

When you run, one of the side effects of running is the production of blood lactate. At low intensity, when you are primarily using oxygen to produce energy, this blood lactate is being processed into a fuel source as quickly as it is being produced. At a certain point, once the intensity rises, the blood lactate begins to accumulate more quickly than it can be processed. Scientifically this point is known as OBLA (onset of blood lactate accumulation) or more colloquially as threshold. Above this intensity the body begins to become increasingly anaerobic, that is to lack sufficient energy produced from oxygen.

Threshold is an intensity that a runner should be able to maintain for 30-60 min. There are various methods of working out one’s threshold. One of the easiest being to see how far/fast a runner can run for 45 min.

The greater ones running economy, the less oxygen that will be required to run at a given intensity, and therefore faster someone will be able to run before they reach threshold.

It is hopefully easy to understand that as intensity increases, our oxygen demand increases, and therefore our running economy at an increased intensity is lower. In turn our capacity to stay there for any length of time decreases.

Intensity is where race strategy comes in to play. There is a common lament amongst runners post event along the lines of “I went out too fast at the start, and suffered towards the end of the event”.

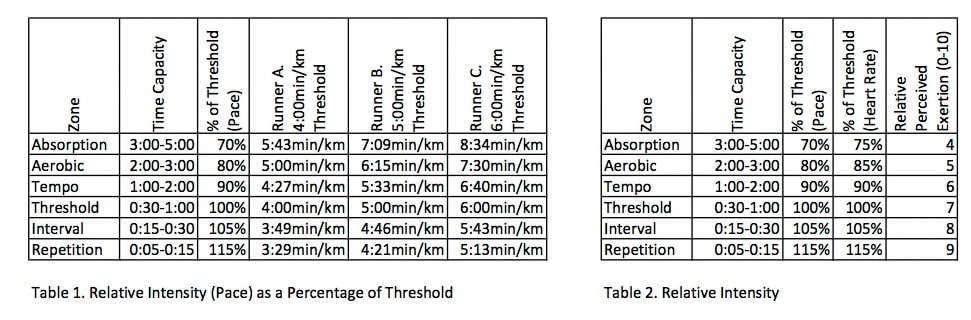

The good news is that for a moderately trained runner, based on their threshold pace, we have a pretty good idea of how long they will be able to stay at a given pace. As an example (see attached table) a moderately trained runner with a 5:00min/km threshold should be able to run on a flat-rolling road course in good conditions for 2 – 3 hours at approximately 6:15 min per km. Of course, that is all well and good if we are running a flat-rolling road run in good conditions, and almost useless if we try and apply it to a trail run.

When you run, one of the side effects of running is the production of blood lactate. At low intensity, when you are primarily using oxygen to produce energy, this blood lactate is being processed into a fuel source as quickly as it is being produced. At a certain point, once the intensity rises, the blood lactate begins to accumulate more quickly than it can be processed. Scientifically this point is known as OBLA (onset of blood lactate accumulation) or more colloquially as threshold. Above this intensity the body begins to become increasingly anaerobic, that is to lack sufficient energy produced from oxygen.

Threshold is an intensity that a runner should be able to maintain for 30-60 min. There are various methods of working out one’s threshold. One of the easiest being to see how far/fast a runner can run for 45 min.

The greater ones running economy, the less oxygen that will be required to run at a given intensity, and therefore faster someone will be able to run before they reach threshold.

It is hopefully easy to understand that as intensity increases, our oxygen demand increases, and therefore our running economy at an increased intensity is lower. In turn our capacity to stay there for any length of time decreases.

Intensity is where race strategy comes in to play. There is a common lament amongst runners post event along the lines of “I went out too fast at the start, and suffered towards the end of the event”.

The good news is that for a moderately trained runner, based on their threshold pace, we have a pretty good idea of how long they will be able to stay at a given pace. As an example (see attached table) a moderately trained runner with a 5:00min/km threshold should be able to run on a flat-rolling road course in good conditions for 2 – 3 hours at approximately 6:15 min per km. Of course, that is all well and good if we are running a flat-rolling road run in good conditions, and almost useless if we try and apply it to a trail run.

When the terrain becomes rougher and more variable we need to start looking at other ways to monitor and moderate intensity. Heart Rate and a Relative Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale are two commonly available methods of measuring intensity that a runner might choose to use in isolation or in conjunction with other factors. RPE is subjective, though I have suggested a scale applying to different zones of intensity. As with pace, using heart rate relies on establishing a threshold heart rate that is able to be maintained for 30-60 min, and then applying relative intensities.

In conclusion, our relative running economy is influenced by regular disciplined training (including strength and drills to improve form), a solid nutritional intake and proper rest and recovery. This increased economy will positively influence our ability to run at a greater relative intensity for longer. Management of that intensity is what will see us have a successful race or a less than positive outcome. I would suggest that working on increasing your running economy over a period of months, to then squander that success with less than considered management of intensity is easily avoidable and will lead to a far more fulfilling end to a schedule of training and racing.

In conclusion, our relative running economy is influenced by regular disciplined training (including strength and drills to improve form), a solid nutritional intake and proper rest and recovery. This increased economy will positively influence our ability to run at a greater relative intensity for longer. Management of that intensity is what will see us have a successful race or a less than positive outcome. I would suggest that working on increasing your running economy over a period of months, to then squander that success with less than considered management of intensity is easily avoidable and will lead to a far more fulfilling end to a schedule of training and racing.